Can South Africa afford another unrest?

Graphic: Timothy Alexander African News Agency (ANA)

By Professor Bheki Mngomezulu

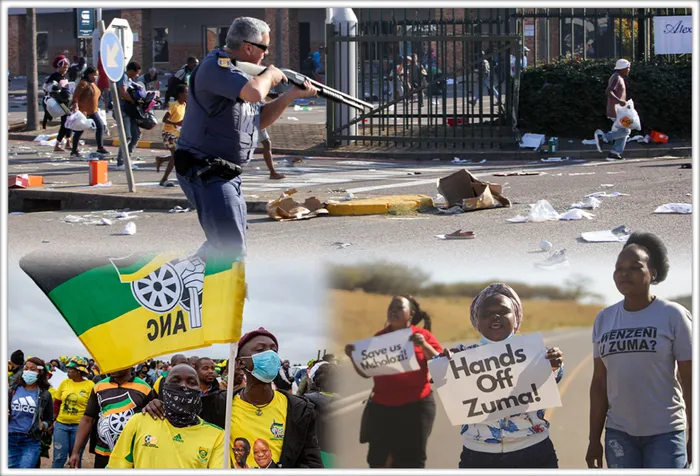

The month of July 2021 has earned itself a place in the South African calendar, albeit for wrong reasons. It was during this time when KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng were engulfed by violent protests of unimaginable magnitude. These protests even surpassed those that happened during the apartheid era.

They seemed to have been well orchestrated and carefully coordinated. The country’s law enforcement agencies were overwhelmed.

In the process, over 350 lives were lost under different circumstances. Racial tensions flared.

KZN alone recorded an estimated damages worth billions as businesses and the infrastructure were completely destroyed. Many jobs were also lost.

To this day, not all business have recovered.

The rebuilding process is currently under way. However, the floods which descended in KZN between April and May 2022 derailed the rebuilding process and compounded the already untenable situation. In essence, the province is still licking its wounds.

Although Gauteng was also affected by an unrest, at least the impact of the recent floods was not as severe in Gauteng as it was in KZN. Therefore, my reflections are primarily focused on KZN but also consider the national context.

As we reflect on the unrest which left KZN devastated, three questions beg for attention.

The first question is: How did we get here? Put differently, who is to blame for this incident? The second question becomes: What did we learn from these unrest as a country? Thirdly and most importantly, have we been able to address all the causal factors so that we could avert a similar incident from happening again?

The reality is that none of these questions is easy to answer. The reason is simple, whatever response one provides is bound to be subjective at best and defensive at worst.

However, this does not mean that we should stop reflecting on this unfortunate incident in preparation for potential similar incidents happening in future. In fact, the current situation in the country looks worse than it was in 2021. Therefore, it is justifiable to be worried about the prospects of another devastating unrest.

One of the theories used in the realm of the International Relations discipline is called Frustration Aggression Theory. It argues that frustration leads to people engaging in activities that are not acceptable.

They do this after failing to find solutions to the challenges they are faced with. All they need is a trigger to set off the ignition. Drawing from this theory, we can ponder about the circumstances which might lead to an unrest.

Firstly, the high rate of unemployment has been a serious concern in South Africa recently. This is caused in part by the slow economic growth. Secondly, corruption in the country has become rampant.

Consequently, some of the money that is meant to uplift society ends in individuals’ pockets.

Thirdly, the level of crime is at an unacceptable level. Coupled with that, the judiciary and the entire justice system has lost credibility among members of the society.

The real and perceived selective application of the law has made people lose confidence in the country’s justice system. Concerns about the calibre of leaders in the country have painted a pessimistic picture and left the majority of South Africans hopeless.

Failure by the political leadership to present clear proposals on how they plan to rescue the country from these and many other challenges does not assist in containing the situation.

Under these circumstances, all that was needed was one trigger to ignite the fire. The questionable circumstances under which former President Zuma was incarcerated became the trigger. The question becomes: who is to blame for this?

The report by then Public Protector Advocate Thuli Madonsela created the impression that President Zuma was the main suspect in the state capture saga. It was for this reason that she did not submit her report to Zuma but rather handed it to the National Assembly Speaker, Baleka Mbete.

After recommending that a Commission of Inquiry should be appointed, she proposed that the judge to chair such a commission should not be appointed by President Zuma but by the Chief Justice of the Constitutional Court. Indeed, this is what happened – thus marking deviation from Section 84(f) of the constitution which empowers the sitting president to appoint the entire commission.

President Zuma appeared before Judge Zondo who had been appointed to chair the Commission into State Capture. During his appearance, Zuma felt that he was not treated like the other witnesses who had appeared before him. He then asked Zondo to recuse himself so that he could present his evidence in a less hostile environment.

Judge Zondo became the referee and the player when he personally considered Zuma’s request and concluded that he was not going to recuse himself. Had he asked someone else to look into the matter in which he was conflicted, the end-result might have been different.

When Zuma failed to appear before Zondo for the second time, Zondo went straight to the Constitutional Court to lay a complaint against Zuma. Secondly, he prescribed a two-year sentence in the event that Zuma was found guilty.

Lawyers would be in a better position to say if this was indeed in order – approaching the Constitutional Court in the first instance and prescribing the two-year sentence.

Some would argue that Zuma was supposed to have respected the Constitutional Court ruling that he should appear again before Zondo despite his disgruntlement.

The concern is that the Constitutional Court ruled that Zuma had forfeited his right to remain silent or not to answer certain questions as had been the case with other witnesses. I am not sure if this would have been a fair process.

I am also not sure if the phrase “everyone is equal before the law” would still be applicable. As Judge Zondo also stated, Zuma was once the president and had appointed the commission. As such, Zondo was infuriated by the fact that, in his view, Zuma was frustrating the commission.

The fairness of such an utterance remains debatable.

Delivering her judgment after Zuma had defied the Constitutional Court ruling, Judge Khampepe was furious! She repeated Zondo’s concerns about Zuma. Khampepe could have imposed a suspended sentence on Zuma without breaking the law. She could have imposed a fine, which is permissible in law. However, she opted to impose a 15-month sentence, thereby unwittingly setting up the fire.

This judgment became the main trigger of the July unrest. Before the judgment was delivered, word circulated that should Zuma be incarcerated, there would be mayhem in the country.

Why was this warning not heeded by state institutions?

Following Zuma’s arrest, word circulated that if he was not released, there would be an unrest in the country. Why was this warning ignored? Throughout this process, Zuma’s lawyers, led by Advocate Dali Mpofu, made vain attempts to rescue the situation. Was there nothing permissible in law to avert this situation? Failure to manage the Zuma matter properly resulted in the unrest and its resultant disaster.

The realities faced by the majority of South Africans became visible during the looting.

While some people looted luxury items, others went for the most basic necessities – with some even stealing disposable diapers for kids! Such incidents laid bare the suffering among many South Africans.

Intriguingly, the police (some of whom were implicated in looting) were instructed to go from house to house collecting the looted goods. No records were kept of the items taken. So, what became of those “collected” goods? How many of them ended in the homes of the police and their friends? What did that say about trust between the police and communities?

What did government do about this? These are some of the critical questions worth answering.

Sine the 2021 unrest, the situation in the country has become worse. South Africa has reached unprecedented level 6 load shedding. Unemployment figures have risen exponentially. Crime statistics are shocking. Floods in provinces such as KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape, Western Cape and others have compounded the problem.

Now, the question becomes: are we better of now than we were in 2021? The answer is an emphatic no! In fact, the situation is worse now than it was in 2021.

As I conclude, let me address the most pertinent question: have we as a nation learnt from the 2021 unrest?

Without being a pessimist, my answer is in the negative. There are a few examples to buttress this assertion.

Some formations still want Zuma back in jail. They don’t bother about the likely impact of their call. Instances of racial tensions are mounting.

A white farmer shot at black people claiming that he mistook them for hippopotamus! Another white man assaulted a 16-year-old boy over salt and pointed a gun at him. The list goes on.

Do we need another trigger to ignite an unrest? Are we slow-learners as a nation? What are we doing to address people’s concerns such as load shedding? We need to wake up before it is too late!

Professor of Political Science and Deputy Dean of Research at the University of the Western Cape.

This article is original to The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.