BRICS stands tall as New World Order emerges

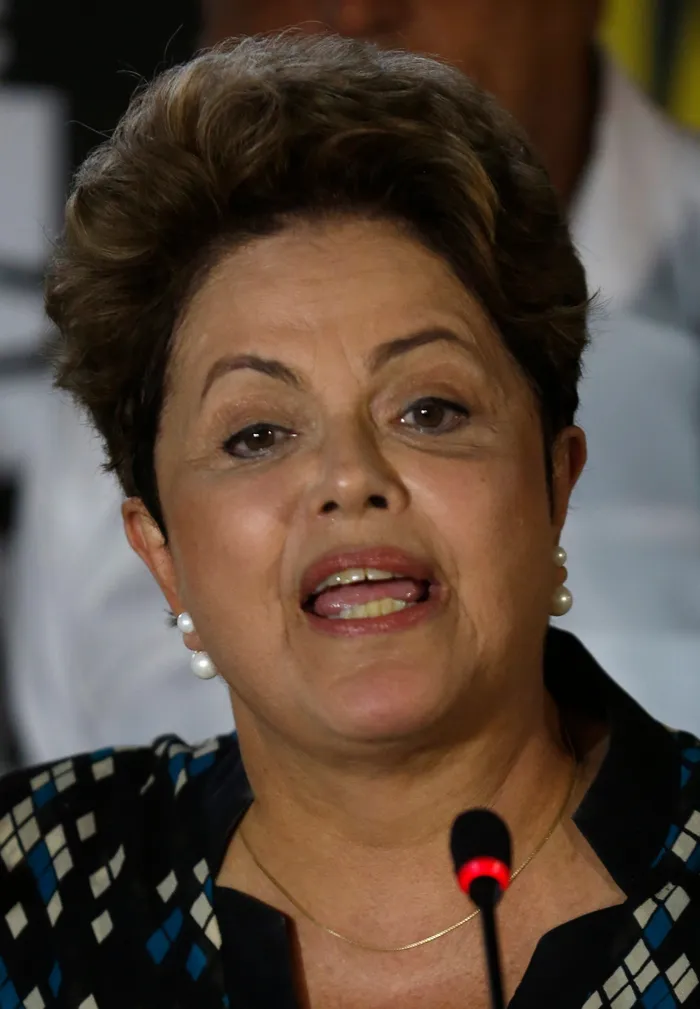

Picture: Pilar Olivares/REUTERS/Taken September 2014 – Former Brazil President Dilma Rousseff has been appointed head of the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) which provides a source of funding for development projects in various countries. It is an alternative to the western-controlled World Bank whose lending practices were increasingly seen as undermining the sovereignty of developing countries.

By David Monyae

The emergence of the BRICS group (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) in the late 2000s was a response to the perceived inequities and flaws of the western-led global order which was biased towards the Global North at the expense of the Global South.

BRICS, a coalition of some of the world’s leading emerging markets, was formed to challenge the dominance of the West in various domains including technology, international trade, international finance, global health, and global security among others. Global South countries became increasingly disillusioned by the US-dominated unipolar post-Cold War global order, which worked to widen the economic inequality between the developed and developing countries.

Under-represented in key global institutions like the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Health Organisations (WHO) to mention a few, developing countries began to call for the reform of the international system. They argued that the US-centred international system framework had become anachronistic, undemocratic, and misaligned with the realities of the evolving global economy.

As such, BRICS was a concrete expression of the long-held desire in the global south to forge an alternative global order responsive to the needs and interests of the poor countries. The new bloc was also a culmination of the rapidly shifting global economic power which saw the rise of new economic centres such as China, India, Brazil, Malaysia, and Indonesia among other countries. While in 2000, the developed countries located mostly in the West contributed 80 percent of the global GDP, this share shrunk to 60 percent in 2019. Other reports have estimated that the economic size of the so-called E7 countries (China, India, Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, Russia, and Turkey) will surpass the G7 (United Kingdom, US, Japan, Italy, Canada, France, and Germany) by 2030. This means that a definitive shift of the global economic power is imminent with significant repercussions for global politics.

In the 14 years it has been existence, the BRICS bloc has been slowly chipping away at the western dominated global order while carving out a niche for itself. During this period the countries have established the BRICS New Development Bank (NDB) which provides a source of funding for development projects in various countries. It is an alternative to the western-controlled World Bank whose lending practices were increasingly seen as undermining the sovereignty of developing countries.

The NDB has approved 11 multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects across the transport and energy sectors in Lesotho and South Africa and even more in other countries. The bloc has also set up the BRICS Contingency Reserve Arrangement (CRA) which is meant to provide liquidity to BRICS countries during times of financial crisis thus reducing dependency on the IMF. Perhaps more significantly, the BRICS group has become more and more vocal about moving away from the use of the US-dollar in their transactions with each other – famously termed, ‘de-dollarisation’.

China and Russia launched a cross-border payment system which saw the use of the dollar decline from 90 percent to 50 percent in the trade between the two countries. One of the outcomes of the 2022 BRICS Summit was the commitment to develop a BRICS Payment System to facilitate trade between the member countries. The group has also expressed serious intentions of establishing a BRICS reserve currency, which will be based on the local currencies of the member countries: the South African rand, Indian rupee, Russian ruble, Brazilian real, and the Chinese yuan.

The prospective reserve currency will see the US$162 billion intra-BRICS trade reducing the dominance of the US dollar and the Euro. What remains is for the countries to build a robust financial infrastructure to make the use of a common currency possible. Contributing more than 25 percent of global GDP, almost 18 percent in world trade and 25 percent in foreign investment, the BRICS group has the economic muscle to transform the global financial system. The push for the de-dollarisation of the international financial system gained momentum in the wake of the US sanctions on Russia after the beginning of its war with Ukraine.

The US leveraged its control of the international financial system to freeze Russia’s assets and also eliminate Russian banks from the Society for Worldwide International Financial Telecommunications (SWIFT) system which made it difficult for Russia to conduct any international transactions. The de-dollarisation campaign is therefore a strategic move by BRICS countries calculated to boost and reinforce their strategic autonomy from the US in terms of their foreign and economic policies.

As the BRICS looks to expand its membership with the admission of other strategic countries such as Argentina, Turkiye, Iran and Saudi Arabia who have shown great interest in joining the group, this will mean more countries and people dropping the dollar thus making the de-dollarisation campaign even more comprehensive.

If the de-dollarisation campaign is successful it would present a serious challenge to American dominance and pave way for even more challenges in technology and security domains. It is within this context that South Africa’s foreign policy emergencies are based. For South Africa, the post 1945 world order should and must be reformed to avoid the capturing of the institutions of global governance.

Prof David Monyae is Associate Professor of Political Science and International Relations, and Director of the Centre for Africa-China Studies (CACS)

This article is exclusive to The African. To republish, see terms and conditions