As crimes against peacekeepers increase, how to find accountability

Source: UN Peacekeeping, “Action for Peacekeeping +: Overview for November 2021-April 2022.”

Picture: Harandane Dicko/United Nations – A peacekeeper works on detecting improvised explosive devices (IEDs) during logistical convoys and long and short-range patrols in central Mali, December 2022.

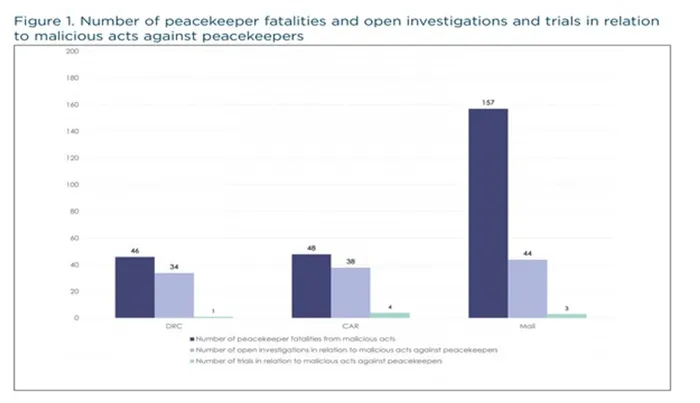

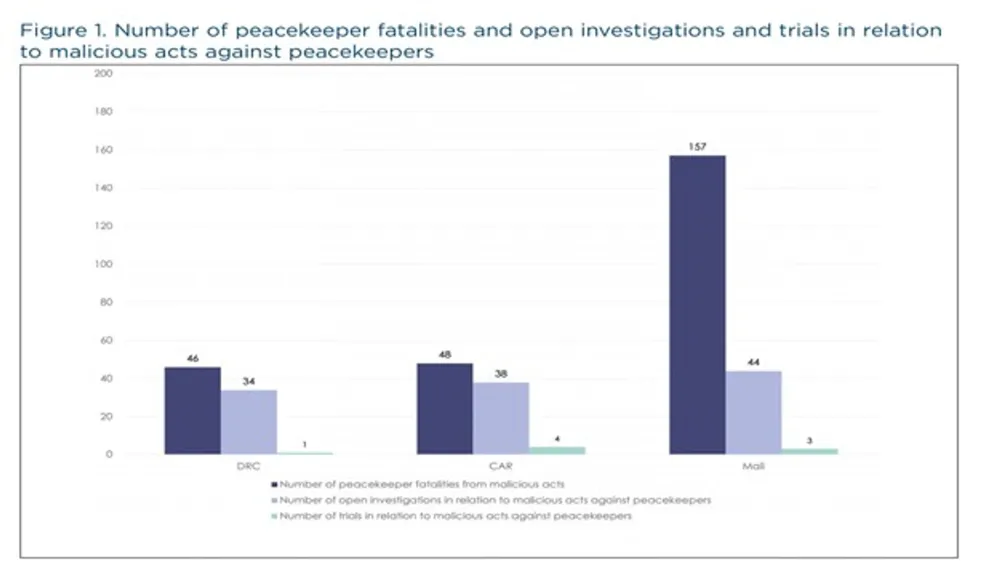

Since 1948, more than 1,000 United Nations personnel have been killed by “malicious acts” while serving in UN peacekeeping operations, and more than 3,000 have been injured. The number of acts has spiked since 2013, with the vast majority of deaths occurring in the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

As noted in the recent report from the International Peace Institute, while some progress is being made to increase accountability for crimes against peacekeepers, major challenges remain, particularly as it relates to justice for peacekeepers. Among other risks, there is a sense that without more accountability for attacks against their uniformed personnel, some troop- and police-contributing countries might withdraw from or be deterred from joining missions operating in non-permissive environments.

High Fatalities, Few Prosecutions

The UN mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is by far the most dangerous mission for peacekeepers, with 172 fatalities resulting from malicious acts since 2013 as of February 2023. However, most fatalities have not been investigated by national authorities, and in the past two years there have been only three convictions related to the death of peacekeepers in Mali.

In CAR and the DRC — which have each seen 51 peacekeepers killed as a result of malicious acts since 2013 — most deaths have been investigated by national authorities, but very few of these investigations have led to suspects being brought before courts, and even fewer have led to convictions.

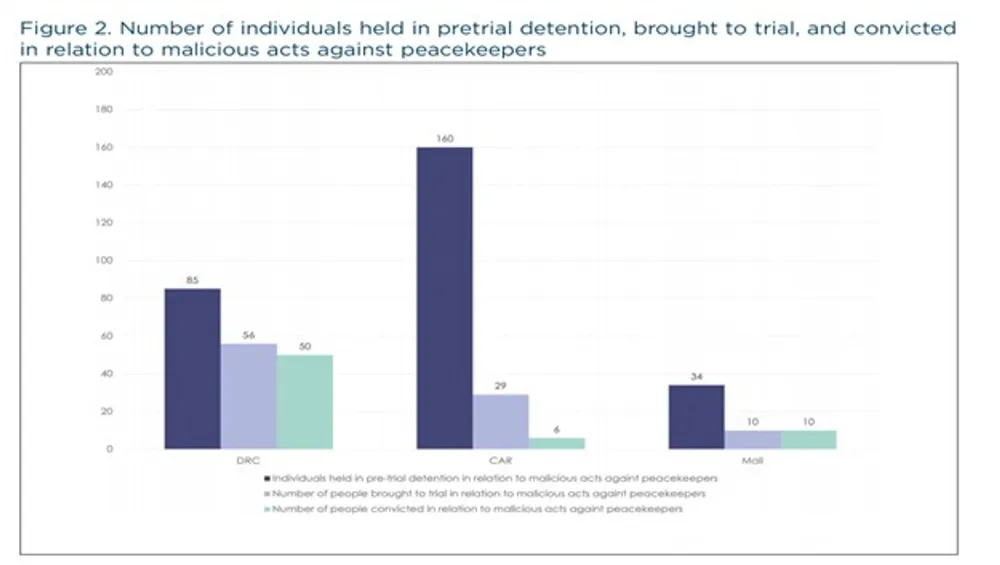

In CAR, while the number of investigations and detentions related to crimes against peacekeepers is the highest among the three missions, the number of convictions is the lowest. Currently, there are thirty-eight investigations into crimes against UN peacekeepers open at the national level in CAR. Progress has varied across each of these investigations, four of which have gone to trial so far, with one resulting in 28 convictions.

Similarly, in the DRC, a sole case led to the conviction of fifty people, which constitutes all the convictions related to fatalities of UN personnel in the country.

Because most attacks against peacekeepers have not led to investigation, prosecution, judgment, and conviction, the following examples from Mali, CAR, and the DRC are exceptional cases. Still, they provide a glimpse into challenges encountered at the different phases of the criminal proceedings once these processes are initiated by the host state.

IEDs, Impunity, and the Need for Prevention

Improvised explosive devices (IEDs) represent one of the biggest threats to the safety of peacekeepers. Since 2014, 643 peacekeepers and UN staff have been injured or killed by IEDs. In 2022, 50 percent of uniformed peacekeeping fatalities from malicious acts were due to explosive ordnance incidents.

IED attacks are some of the most challenging to investigate and prosecute due to how difficult it is to trace the attack back to specific perpetrators. To do this, evidence needs to be collected and analysed, but host states usually lack specialised agents outside of their capitals — something that can be further complicated by a lack of state presence in parts of the country and ongoing fighting.

In Mali alone, more than 93 peacekeepers have been killed by IEDs, which are often planted along the routes used by MINUSMA convoys for patrols, including as part of the mission’s protection of civilians (POC) mandate. Only one of these attacks resulted in a prosecution, which was secured through an individual confessing to laying mines during a preliminary investigation. The individual was sentenced in absentia to life in prison in 2020. To date, this is the only conviction made following the investigation of an IED attack against peacekeepers in Mali, CAR, or the DRC.

A recent IED attack in CAR demonstrates the challenges not only of investigating IED attacks but also of ensuring the safety and security of peacekeepers. In October 2022, three soldiers dispatched on a POC patrol were hit by an IED explosion. The soldiers were seriously injured and died after their evacuation to a hospital was delayed by the government’s ban on the UN mission (MINUSCA) conducting night flights. Following their deaths, the national judicial authorities in CAR requested MINUSCA support the judicial process under the mission’s urgent temporary measures. The mission was thus able to start collecting evidence at the crime scene, with the support of the UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS) and MINUSCA’s forensic police (MINUSCA is planning to establish an IED forensic lab to facilitate such investigations in the future). While the outcome of this case is pending, investigators have faced challenges gathering evidence in locations controlled by armed groups, which can make local populations afraid to talk to them due to fear of retaliation.

Despite the increasing capacity of missions, the hope for accountability and justice is low once an attack has been committed. One MINUSMA official noted that “those who plant IEDs are living in complete impunity, unless we find the mines in their house or where they fabricate the mines, or they confess”. There is therefore a sense that the UN has no choice but to focus on reinforcing the safety and security of peacekeepers to prevent attacks and casualties in the first place.

Legal Ambiguities and State Discretion in Prosecutorial Strategies in Mali

In May 2015, a shooting took place at the residence of peacekeepers in Faso Kanu, Bamako, injuring a guard. Five days later, a MINUSMA vehicle was shot at in Sénou, Bamako, killing one peacekeeper and injuring another. Mali’s Specialised Judicial Unit Against Terrorism ultimately took charge of the investigation and prosecution.

The case resulted in nine individuals being convicted for terrorism-related crimes in March 2021, primarily due to their affiliation with Ansar Dine, which is regarded as a terrorist group by the Malian government and is sanctioned by the UN Security Council under its Islamic State and al-Qaida sanctions regime.

Certain factors may have facilitated the investigation and prosecution of these attacks. Contrary to most IED attacks, this attack took place near the capital. Moreover, as opposed to IED attacks, which are anonymous, shootings may be easier to attribute and therefore to investigate and prosecute. However, eight of the accused were tried in absentia, which raises questions about the effectiveness of the process in preventing those individuals from perpetrating additional attacks in the future.

All recent crimes against peacekeepers in Mali have been prosecuted as terrorism-related crimes because of the individuals’ association with or membership in a designated terrorist group. While this may prove to be an effective and pragmatic prosecutorial strategy, it raises questions about the qualification of the crime. If MINUSMA enjoys protected status under international humanitarian law (IHL), the killing of the peacekeepers should fall under the definition of war crimes or crimes against protected UN personnel.

If MINUSMA has become a party to the conflict and has lost its protected status, the decision of how to qualify such attacks remains at the discretion of the state. However, states’ tendency to define situations of armed conflict through a counter-terrorism lens can weaken respect for IHL, human rights, and support for conflict resolution processes. This is a sensitive question that requires balancing legal principles with policy and practical considerations.

Urgent Temporary Measures to End Impunity in CAR

In May, 2017, five MINUSCA peacekeepers (four Cambodian and one Moroccan) were killed when hundreds of anti-Balaka fighters attacked their convoy near Yogofongo village, 474 kilometers east of Bangui, while they were travelling between Rafaï and Bangassou. An additional ten peacekeepers were injured (nine Moroccan and one Cambodian), and a Moroccan peacekeeper was reported missing in action. There had previously been attacks against the Moroccan contingent, which the attackers suspected of colluding with and providing war materiel to ex-Séléka rebels.

From 2017 to 2019, MINUSCA supported the Central African authorities in investigating the attack, arrested more than fifty suspects and transferred them to government authorities, and supported the government’s prosecution. On February 7, 2020, twenty-eight of the thirty-two militia members put on trial were sentenced for a variety of charges, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crimes against people under international protection, with sentences ranging from ten years to life in prison.

These convictions were lauded by the UN as progress toward ending impunity in CAR. It is one of the rare cases in CAR where investigation and prosecution have led to a conviction. Some of the factors that might have enabled this outcome include the modus operandi of the crime and the strong involvement of MINUSCA under its urgent temporary measures, which enable MINUSCA to perform law enforcement functions, including the investigation and arrest of suspects at the formal request of government authorities and in areas where national security forces are not present or operational. While the authority to take urgent temporary measures is unique to MINUSCA — and should not necessarily be replicated in other contexts, as it raises numerous questions about the legal responsibilities of the UN mission — these measures have helped the mission pursue accountability for crimes against peacekeepers in CAR.

Legitimacy, Consent, Accountability

Throughout 2022, anti-UN protests took place across the DRC. This anti-UN sentiment has been fuelled by the waning consent of the host-state government for the mission’s presence, overall frustration with decades of international presence, and disinformation against the UN mission (MONUSCO). On July 26, 2022, multiple MONUSCO bases across North Kivu were attacked by groups of protesters, leading to looting and destruction of UN properties and resulting in the death of three peacekeepers in Butembo.

Following the attack, the secretary-general recalled the SOFA, which “guarantees the inviolability of United Nations premises,” and called for an investigation, which has since been opened by national authorities. However, MONUSCO has temporarily left Butembo, and the mission’s mobility has been restricted, impeding its ability to directly assist national authorities with the investigation.

In addition to the deaths of UN personnel, the demonstrations led to civilian deaths, and there is controversy over whether these could be attributed to the armed response by peacekeepers. A few days later, in a separate incident, MONUSCO troops opened fire at a border post, killing two people and injuring fifteen others. These military personnel are under the exclusive criminal jurisdiction of the troop-contributing country. The special representative of the secretary-general for MONUSCO and the secretary-general immediately condemned the act, and those responsible have been arrested and suspended until the finalisation of the investigation.

These two cases highlight the crisis of legitimacy the UN is facing in some of the countries in which it operates. It underscores the need to advance accountability of peacekeepers and accountability to peacekeepers simultaneously, as two sides of the same coin. Further, it raises questions about the possibility of advancing accountability to peacekeepers in a context where the host state’s consent to the UN presence is diminishing and it might be reluctant to investigate certain crimes for political reasons. This raises more fundamental political and strategic questions about the UN’s presence in such contexts.

A Sole Instance of Accountability in the DRC

In the DRC, the sole convictions for the killing of UN personnel were for the assassination of two international UN experts (not peacekeepers) and four Congolese nationals who were accompanying them in Kasaï-Central province in 2017. This case is different from the others in that it involves the murder of UN civilian staff who were not part of the UN peacekeeping operation. The two UN personnel — nationals of Sweden and the United States (US) — were part of a group of experts investigating allegations of the excessive use of force by the Congolese military against militias and civilians, mass graves, and the recruitment of child soldiers.

In the days immediately following the group’s disappearance, MONUSCO created a task force to locate them. The six bodies were found in a shallow grave on March 27, 2017. In April, the secretary-general formed a board of inquiry, eventually appointing a team of four technical experts who remained in the country for three years to support the investigation, which was instrumental in moving the criminal proceedings forward. Further, Sweden and the US — two influential states with leverage over the UN system and the host state — put diplomatic pressure on the Congolese government to investigate and render justice for this crime.

Ultimately, forty-nine people were sentenced to death — several in absentia — while one officer received ten years in prison for violating orders, and two others were acquitted. They included alleged members of the Kamuina Nsapu militia, which was involved in the killings, and were convicted of criminal conspiracy, participation in an insurrectionary movement, terrorism, and “the war crime of murder”. Due to a 2003 moratorium on the death penalty in the DRC, they are likely to serve life in prison.

As of the time of writing, no other trials for attacks on UN personnel have even been opened in the DRC. The lack of similar trials for other attacks on UN personnel demonstrates the challenges of pursuing accountability. The case has also raised sensitive questions around Congolese authorities’ consent to the UN presence and willingness to genuinely support the investigation and criminal proceedings.

While many regarded the investigation and trial as important steps for accountability, some human rights groups have questioned whether full responsibility for the killing has been established, pointing to the possible involvement of senior Congolese officials. Further, they have raised concerns around due process and the rights of some of the defendants throughout the proceedings, including their lack of legal representation, as well as torture and cruel treatment.

Next Steps

While some progress is being made, major challenges remain, particularly as it relates to pursuing justice for peacekeepers who have been victims of attacks. Among the challenges is a lack of consistency in the definition of “crimes against peacekeepers”. Another concern is that, while UN missions can support national authorities — who bear the primary responsibility — in investigating and prosecuting crimes against UN peacekeepers, there is a risk of UN missions supporting host-state institutions that violate the rights of the accused. Moreover, difficulties can arise when consent for the UN’s presence is weak. Host states may also lack the necessary capacity in their police, judiciary, and corrections systems. Finally, it is challenging for missions to pursue a holistic approach that includes a focus on preventing attacks and on pursuing accountability not only to but also of peacekeepers — treated as two sides of the same coin under the Action for Peacekeeping Plus (A4P+) priorities.

In light of these challenges, the following recommendations are offered to help the UN Secretariat, peacekeeping operations, the Security Council, and other member states accelerate the investigation and prosecution of crimes against peacekeepers in a consistent and balanced manner.

First, the UN Secretariat should maintain a comprehensive approach to accountability, develop a common definition of crimes against peacekeepers, ensure that host states adhere to human rights standards when engaging with those accused of crimes against peacekeepers, and improve internal and external coordination in this area.

Second, UN missions should pursue a comprehensive approach to accountability, continue to support host-state investigations and prosecutions of those accused of crimes against peacekeepers, advocate for host-state authorities to pursue accountability, and ensure sustained documentation of and follow-up on cases.

Third, the Security Council should prioritise peacekeeping mandates to build the host state’s capacity to pursue accountability and encourage legal clarity on the nature of crimes against peacekeepers.

Finally, UN member states should use the group of friends to offer new ideas on ways to promote accountability and use the Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations to discuss ways to improve coordination in this area.

Agathe Sarfati is Senior Policy Analyst at the International Peace Institute. The article was based on her March 2023 IPI report Accountability for Crimes against Peacekeepers. Jill Stoddard is Editor-in-Chief of the Global Observatory.

This article was first published on Global Observatory