African leaders ‘must speak in one voice’ when engaging China over policy

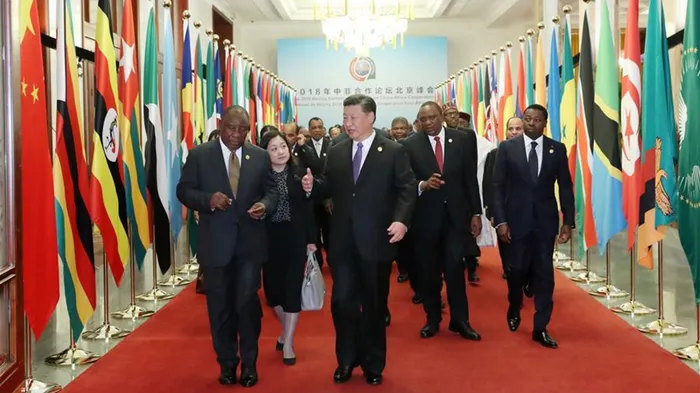

Chinese President Xi Jinping with President Cyril Ramaphosa, right, and other foreign leaders attend the opening ceremony of the Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China, September 3, 2018. – Picture: Xinhua

By Sizo Nkala

The biggest of the so-called “Africa + 1 Summits”, the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac), is set to take place in Beijing early next month. The last meeting was hosted by Senegal in 2021.

Now in its ninth instalment over 24 years, the summit has become an embodiment of South-South co-operation and a crucial co-ordinating platform for driving China-Africa relations forward. The Beijing meeting will be the fourth head-of-state summit under the Focac framework with 2006, 2015, and 2018 meetings upgraded to head-of-state summits.

Although the Focac is still an informal arrangement with no treaty or permanent secretariat, its regularity – it has been convened unfailingly every three years since 2000 – gives much-needed stability and predictability in the interactions of the two sides.

This is why we have seen the steady growth of Sino-African relations since the turn of the twenty-first century across diplomatic, economic, security, culture and development spheres.

Over the years, the Focac has grown in size and sophistication. While the first Focac was attended by 44 African states, the 2021 meeting attracted 53 states including the AU Commission.

The content and the agenda have also expanded significantly, demonstrated by the length of the Action Plan document increasing from just 3,000 words in 2000 to over 12,000 in 2021. Notable changes in the content of Action Plans have been observed in the last two and a half decades.

For example, in the economic sphere, the 2000 Action Plan focused on traditional issues such as trade, investments, infrastructure and development finance, while subsequent documents incorporated non-traditional issues such as digital technology, green development, blue economy, customs supervision, and industrial capacity co-operation.

In the security arena, the Action Plans have expanded traditional security issues to incorporate arms trafficking, illegal immigration, disease pandemics, law enforcement, policing, natural disasters and anti-corruption.

Impressively, while in its early days, the Focac was a top-heavy inter-governmental affair, political co-operation has devolved from the predominantly government-to-government format to include lower-level co-operation involving legislatures, political parties, judicial institutions, local government, the AU and the various regional economic communities. Co-operation in areas including news and media, youth and women and environmental protection was first mentioned in the 2006 Plan.

The 2009 Plan introduced the people-to-people and cultural exchanges segment signifying a qualitative change in the relationship that was widely viewed as too formal and oriented towards high-level politics.

Moreover, the Focac is becoming increasingly institutionalised and complex with 28 sub-forums including China–Africa People’s Forum, the China-Africa law enforcement and security forum, and the China-Africa peace and security forum among others. The sub-forums drive the China-Africa agenda in specific areas.

There are also structures such as the China-Africa Joint Business Council, China–Africa Products Exhibition Centre, China-Africa Chamber of Industry and Commerce and the China-Africa Youth Festival which contribute to growing the relationship.

There are special funds like the China-Africa Peace and Security Fund, the China-Africa Fund for Industrial Co-operation, the Africa Growing Together Fund and the China-Africa Development Fund which ensure the allocation of resources to specific areas.

Most of the issues that make it to the Action Plan are first discussed in these structures. The sub-forums such as the China-Africa Economic and Trade Co-operation Forum,

China-Africa Think Tanks Forum and the Forum on Global Action for Shared Development have already held meetings in preparation for the summit.

From an African perspective, high on the agenda this year will be economic co-operation. Africa’s economic growth slowed in 2023, growing by 3.1% from 4.1% in 2022, which was due to external shocks such as high energy and food prices and a debt crisis affecting over a third of African countries.

As such, enhancing co-operation on trade, investment, industrialisation, development finance and infrastructure will be of interest to African countries.

Moreover, the Forum comes amid a global order in a state of flux marked by growing tensions between major countries and the erosion of multi-lateralism at the global level.

The Focac is likely to reiterate the solidarity the two sides have consistently pledged since the inaugural meeting in 2000 on various global issues including peace and security, climate change and the reform of global governance institutions.

Disappointingly Africa is going into another Focac gathering without a Common African Position on China. Lacking a coherent strategy, African countries end up competing for bilateral deals with China based on their narrow national interests which produces sub-optimal outcomes for the Continent.

Just like China has produced three Africa policies, African nations needs to go to Focac armed with a China policy which will see leaders speak with one voice.

* Dr Sizo Nkala is a Research Fellow at the University of Johannesburg’s Centre for Africa-China Studies.

** The views expressed in this article are those of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of The African

Related Topics: