UN at a Crossroads: Birth Pangs of a New World Order

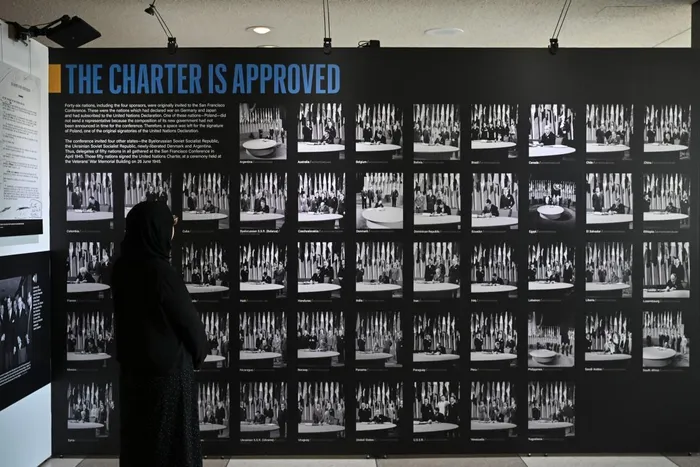

A viewer looks at the “UN Charter” exhibition ahead of the 80th anniversary of its signing at the United Nations Headquarters on June 20, 2025 in New York.

Image: AFP

Clyde N.S. Ramalaine

As the United Nations approaches its eightieth anniversary, with its High-level Segment meeting held this week from September 23–29 under the theme: “Better together: 80 Years and more for peace, development and human rights”, the milestone invites both celebration and sober critique.

Established in 1945 amid the ruins of World War II, the UN embodied the hope that humanity could transcend the cycles of conflict and forge a cooperative order grounded in peace, justice, and dignity. Central to its mission was the principle of multilateralism: the belief that global challenges, from war to poverty, human rights to climate change, require collective action under shared rules.

Eight decades later, the UN stands as both an emblem of aspiration and a reflection of constraint. It has evolved, expanding membership, broadening its agenda, and shaping global norms, but also devolved, with institutional paralysis, selective enforcement, and bureaucratic inefficiencies undermining its authority. The UN at eighty embodies a paradox: a platform designed to unite humanity that simultaneously exposes the limits of cooperation in a fragmented, multipolar world.

Origins and Purpose

The UN’s founding Charter declared the determination of nations to save succeeding generations from war, uphold human rights, promote justice, and advance social progress. Its raison d’être was fourfold: maintain international peace, protect human dignity, foster cooperation, and serve as a centre for harmonising national actions.

The Charter reflected lessons from the League of Nations, aiming to anchor global security in collective rules rather than raw power. Yet, as Boutros Boutros-Ghali noted, the organisation was always constrained by the dominance of its most powerful members, particularly the Security Council’s permanent five, [China, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America] whose interests often overshadowed global justice.

Evolution: Adaptation and Norm-Building

The UN’s evolution is evident. From 51 members in 1945 to 193 today, it mirrors the decolonisation wave and the assertion of sovereignty by newly independent states. Its agenda has expanded from peace and security to include development, human rights, climate change, and humanitarian relief. Normative contributions such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Sustainable Development Goals highlight its role in shaping global consciousness.

Even during the Cold War, when superpower rivalry paralysed the Security Council, the UN provided a platform for newly independent states to demand self-determination and economic justice. Post-1991, optimism briefly surged: peacekeeping expanded, humanitarian interventions increased, and human rights mechanisms gained traction. Multilateralism grew to include regional organisations, informal coalitions, and civil society networks. By these measures, the UN has evolved into a sprawling, if sometimes unwieldy, centre of global governance.

Devolution: Structural Constraints and Paralysis

Yet this evolution has been accompanied by severe constraints. The Security Council remains trapped in 1945 geopolitics. The veto power of the permanent five frequently overrides both the moral authority of the UN Charter and the wider membership’s aspirations, entrenching paralysis during crises from Syria to Ukraine.

The failures extend beyond the Council. The UN has repeatedly stood by during genocides, invasions, and humanitarian catastrophes: Rwanda (1994), Srebrenica (1995), Iraq (2003), and Myanmar in recent years. Peacekeeping missions, once celebrated, now often exemplify dysfunction, prolonging conflict, exposing civilians to abuse, or failing to enforce mandates. Bureaucratic sprawl has further diluted effectiveness: aspiration often exists without enforcement, dialogue without decision, and presence without power.

Multilateralism in Transition

Multilateralism, the recognition that certain problems cannot be solved unilaterally, remains the UN’s central ethos. Historically, it reflected a willingness by member states to cede aspects of sovereignty to prevent war and promote welfare. Today, however, nationalism, populism, and great-power rivalries weaken collective resolve.

For many in the Global South, multilateral frameworks too often shield the interests of wealthier nations while limiting avenues for genuine influence. This frustration has given rise to alternatives. The BRICS coalition, for example, has evolved into a political counterweight, offering emerging powers a platform less dominated by the West. Small island states, meanwhile, have leveraged UN forums to lead global climate debates, illustrating both the possibilities and frustrations of multilateral engagement.

To its defenders, even symbolic UN action carries weight, conferring legitimacy and a platform for the voiceless. Yet symbols without enforcement risk eroding trust, particularly when the organisation cannot deliver protection in moments of deepest crisis.

Contemporary Geopolitical Realities

The UN turns eighty amid undeniable fragmentation. Wars rage across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa; climate disasters intensify; humanitarian crises displace record numbers; and new technologies outpace regulation. The organisation is constantly called upon to act, yet often lacks authority or unity. Samantha Power’s reflections on Rwanda and Srebrenica highlight how UN inaction can hollow out its legitimacy.

The post-Cold War moment briefly offered clarity of purpose. Today’s multipolar order, defined by U.S.-China rivalry, Russia’s assertiveness, and the growing voice of middle powers, creates a fractured landscape where the UN risks being sidelined. Parallel institutions like BRICS challenge its primacy, offering more responsive platforms for Global South priorities.

Reform Imperatives

If the UN is to remain relevant, reforms are not optional but existential. The Security Council must expand to include permanent representation from Africa, Latin America, and South Asia, alongside accountability for veto use. The system requires rationalisation: agencies must be streamlined, duplication reduced, and efficiency improved. Funding should be predictable, adequate, and fairly distributed. Legitimacy must be broadened, empowering the Global South, small states, civil society, youth, and indigenous communities.

Emerging challenges such as climate governance, digital technologies, pandemics, and biosecurity demand agile, enforceable frameworks. Accountability must be strengthened: states that violate international norms should face real consequences, while the UN must transparently address its own failures.

Renewal or Retreat

At eighty, the UN stands at a crossroads. Its founding vision, to prevent war, protect rights, and foster cooperation, remains urgent, yet its structures are straining under modern realities. Evolution is visible in its expanded scope, normative influence, and embedded multilateralism. Devolution is evident in paralysis, great-power rivalry, inefficiency, and the rise of competing forums.

By 2030, two futures are imaginable. In one, the UN adapts: a reformed Security Council includes Africa and Latin America, climate governance is institutionalised, and the UN reclaims legitimacy as the premier global forum. In the other, the UN retreats: veto-bound paralysis persists, regional blocs or ad hoc coalitions handle emerging crises, and the UN becomes a symbolic echo of a past order.

In a form of realistic pessimism, however, one must ask: Is it fair to expect the UN to change in five years what it has struggled to achieve in eighty? The structural inertia of the institution, entrenched interests of great powers, and deep divisions between North and South suggest that reform will be incremental at best.

The choice remains stark. Renewal requires courage, inclusivity, and reform. Retreat invites irrelevance. Yet the more probable outcome may be neither bold renewal nor outright collapse, but slow adaptation, piecemeal reforms that preserve the UN’s existence while leaving its effectiveness in doubt. At eighty, the UN is still indispensable, but its survival will likely rest not on sweeping transformation, but on its ability to bend modestly with a fractured century.

* Clyde N.S. Ramalaine is a theologian, political analyst, lifelong social and economic justice activist, published author, poet, and freelance writer.

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.