Challenges Ahead for the Madlanga Commission: Extended Timelines Expected

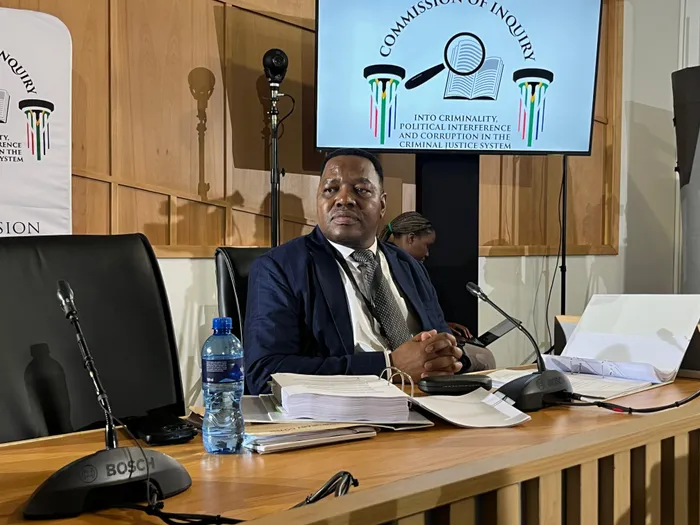

National Police Commissioner Fannie Masemola in the hot seat as he commenced with his evidence at the Madlanga Commission in Pretoria today (Monday).

Image: Kamogelo Moichela/IOL Politics

Prof Dirk Kotzé

Last Wednesday, the judicial commission of inquiry, chaired by Judge Madlanga, commenced with its hearings related to the statements made in early July by Lt Gen Mkhwanazi. When President Ramaphosa announced the commission, the public’s response was not wholeheartedly in favour of it. The question is: why?

Firstly, in the past two decades, quite a number of judicial commissions of inquiry were established by the President. They included the Seriti commission (for the Arms Deal), the Mpati commission (for the Public Investment Corporation), the Farlam commission (for the Marikana massacre), the Nugent commission (for the SA Revenue Service), and the Zondo commission (for state capture).

These were costly exercises and took very long to conclude their work (often well beyond their original timeframe). In several instances, their recommendations were also not fully implemented or acted upon. These are all reasons for the reservations regarding the current Madlanga commission.

What is a judicial commission of inquiry in South Africa? It is directed by the Commissions Act of 1947 and implemented by a presidential proclamation published in the Government Gazette, in which a commission’s terms of reference are set out.

Such a commission can be either a fact-finding mechanism or can investigate a particular event or development of national importance for which an independent process is required. Irrespective of what its specific objective is, the controversial or delicate nature of the issue implies that it cannot be investigated by a government or state institution or officials. The independence of a judge (mostly a retired one) is therefore required to enhance the public trust in the outcome.

Testimonies or evidence presented to such a commission are done under oath. Violation of such an oath by lying or misrepresentations is legally regarded as contempt, and the implicated person can be imprisoned, as former President Jacob Zuma. Persons who can provide such a commission with relevant information can also be summoned by it, even if it is against their will. The Madlanga commission, therefore, does have sufficient powers to address its terms of reference.

The Commission’s terms of reference are wide-ranging and divided into seven components.

The first is to determine whether crime syndicates have infiltrated or developed an influence over the SA Police Service, the metropolitan police services in Johannesburg, Tshwane, and Ekurhuleni, the National Prosecuting Authority, State Security Agency, any member of the judiciary, or the Department of Correctional Services.

Secondly, it should determine the nature, consequences, and extent of such influence. Thirdly, investigating the role of senior officials in the mentioned state institutions in aiding such crime syndicates, or neglecting to act on intelligence and internal warnings, or benefiting in any way from the syndicates’ activities.

Fourthly, the Commission has to investigate the possible involvement of ministers or other senior officials responsible for the criminal justice system in the criminal activities of the syndicates. Fifthly, determining the efficiency or failure of the existing state oversight systems.

The sixth component is to determine the adequacy of the existing legislation, policies, and institutions to prevent criminal infiltration into the criminal justice system. Finally, the commission can make recommendations regarding specific implicated individuals and their continued employment status in the public sector.

This commission will be confronted with two very sensitive challenges. The first one is that the commission has the power to summon witnesses to appear before it or to produce documents to it.

At the same time, it has the power of search and seizure of premises to acquire evidence. That might involve whistleblowers as well as persons who have to do it against their will. The commission will have the responsibility to guarantee their physical safety, taking into account that it might provoke actions from some criminal syndicates.

The second sensitivity is that classified or very sensitive information will become part of the commission’s investigations. Given the focus on SAPS, the NPA, the state, and crime intelligence services and other state institutions, national security considerations will most certainly be at stake.

Judicial commissions, in most instances, conduct their work in public, like most judicial processes, because they are in the public interest and they assist in cultivating public trust in the processes. Classified information will most likely require that the commission also use closed sessions. The decision of what will be public and what will be closed will require sage wisdom.

Looking at the public expectations of what the Commission can achieve, what are the answers the public is looking for?

The first is: were ministers, especially those of police, captured by criminal syndicates, and did they influence their decisions or even assist the criminals in their activities? That can be in the form of corruption, turning a blind eye to specific issues, or taking decisions that favoured the criminals or paralysed police actions.

The second is: were senior police officials complicit in such activities through active support, lack of dedication, or active response to crime activities? Did senior police officials undermine the SAPS’s efficiency in combating crime through their own participation in the crimes or being corrupted by the syndicates? Can they be linked to the drug and gun cartels in different parts of South Africa? Or the political killings and killings of DJs and owners of nightclubs and the private security industry?

The third is: will it be possible to map a second form of state capture of persons and institutions in the criminal justice system by syndicates or cartels, both inside and outside South Africa?

It is unlikely for the commission to complete this complex task within its timeframe of six months. The public’s expectations should therefore be managed, but if the commission can start to provide answers to some of the issues, and they can serve as a warning to the perpetrators that their activities have been exposed, even without a definitive solution, this commission would have already contributed.

* Prof Dirk Kotzé, Department of Political Sciences, Unisa

** The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of IOL, Independent Media or The African.