Famous artist designs racial justice windows for National Cathedral

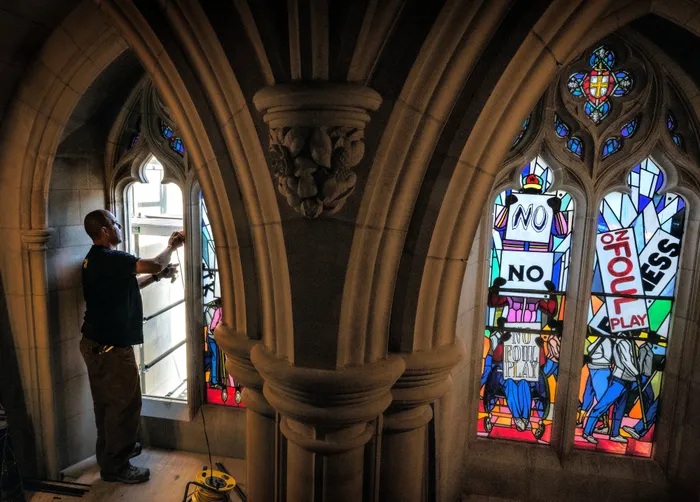

Picture: Bill O'Leary/Washington Post – Andrew Goldkuhle installs glass windows designed by artist Kerry James Marshall at the National Cathedral last month. The new windows dedicated to racial justice were unveiled seven years after the cathedral started reconsidering its Confederate imagery in light of heightened racial tensions across the nation.

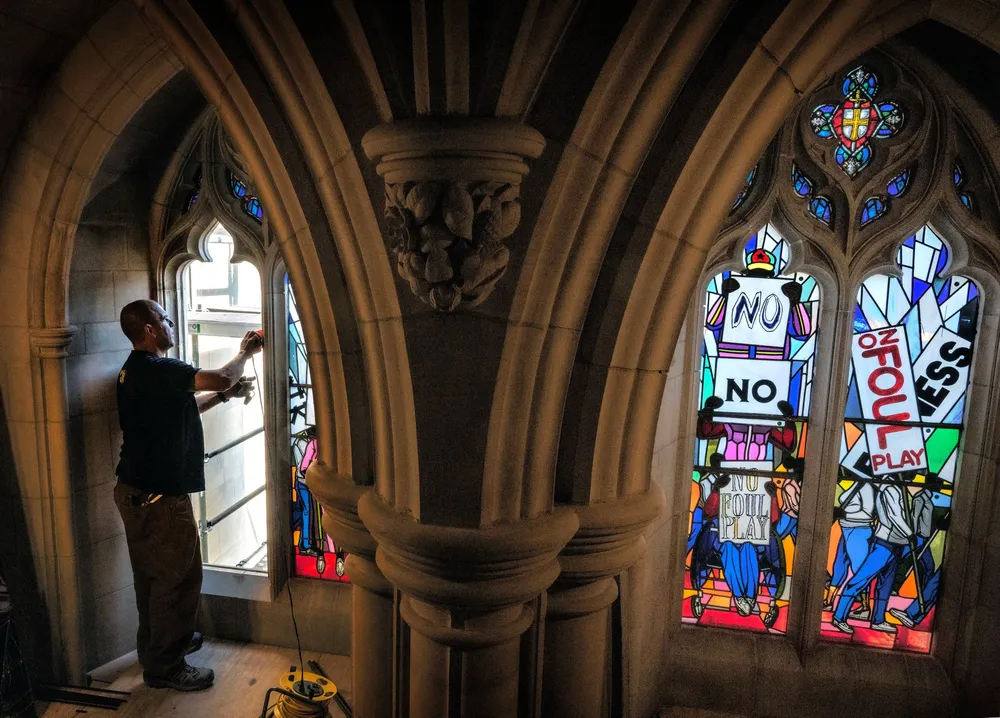

Picture: Jonathan Mehring/The Washington Post – Artist Kerry James Marshall, with a stained-glass window he designed.

By Marisa Iati

WASHINGTON – His paintings sometimes sell for millions. This one went for $18.65.

Kerry James Marshall, whose works have adorned the walls of national galleries and celebrities’ mansions, couldn’t imagine charging Washington National Cathedral his usual fee to replace its Confederate-themed windows. Instead, he requested a commission symbolising 1865, the year the nation’s last enslaved African Americans were liberated at the conclusion of the Civil War.

“It’s a full payment that I can accept as a completely free individual, able to make decisions about myself and the things I do and who I do it for,” Marshall said. “I’m completely free. And that’s what the end of the Civil War represents on a lot of levels.”

The cathedral, one of the country’s most prominent houses of worship, unveiled the two new stained-glass windows Saturday, seven years after it started reconsidering its Confederate imagery in light of heightened racial tensions nationwide. In 2021, the church tapped Marshall to design a glass-and-paint creation to go where images of Confederate generals Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson once stood.

At the service Saturday, Dean Randolph Hollerith recounted how the cathedral came to remove the Lee-Jackson windows after the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville.

“Simply put, these windows were offensive,” he said. “They were intended to elevate the Confederacy, and they completely ignored the millions of Black Americans who have fought so hard and struggled so long to claim their birthright as equal citizens.” The new windows, he said, tell a different story, one “that lifts up the values of justice and fairness and the ongoing struggle for equality among all God’s children”.

Prominent African Americans, including Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, gave readings as part of the service. Jackson read an excerpt from the Rev Martin Luther King Jr’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

Marshall also spoke. “The cathedral stands for what the nation stands for and what I hope we all as members of this culture and society will embody and stand for and bring forward ourselves.”

Church leaders gave Marshall a sweeping mandate: to “capture both darkness and light, both the pain of yesterday and the promise of tomorrow, as well as the quiet and exemplary dignity of the African American struggle for justice and equality” and its impact on the nation.

The four panels Marshall created in response, titled “Now and Forever”, depict Black Americans marching with handmade signs reading “Fairness”, “No foul play” and other similar language. Overlapping shapes create frenetic energy, with warmer colours lower on the windows and cooler hues higher.

The aim, Marshall said, was to reflect the active nature of seeking justice in a nation that never quite sticks the landing.

“You have to strive for justice. It’s not something that is just there,” he said. “It just seemed to me that if I was going to have the windows really embody the concept, they had to really address the activity.”

Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, an art historian at the University of Pennsylvania who served on the cathedral’s window-replacement committee, said Marshall was an obvious choice to design the new windows. The group wanted someone whose work would feel eternal and centre the Black cultural legacy while speaking to a broad audience.

As one of the nation’s most prominent African American artists, Marshall fit that mission, Shaw said.

“I really felt that he would be an artist who wouldn’t see this as an opportunity to increase the prices of his work or to showboat his aesthetic and artistic abilities in a way that was self-celebratory,” she said, “but rather that he would understand the deep meaning of this commission of something that would endure for a thousand years or more, provided he got it right.”

Cathedral leaders were thrilled when Marshall agreed to the project and submitted a sketch of his vision, Hollerith said. They didn’t ask him to make a single change, in contrast to some partnerships with other artists in which designs have undergone four or five iterations.

Inside a cramped garage near Richmond in June, Marshall used a roller to spread black paint on a piece of yellow foam. He pressed a printing block into the dye – composed of ground glass and a binder – and carefully matched it to the spot on the glass where a character’s face should be.

Behind the windows, Andrew Goldkuhle held up a white panel to reflect the sun.

“Does that brighten it up at all, Kerry?” he asked. “Just putting that white thing on there so you can see the face better?”

“Yeah, it does,” Marshall said. “It helps some.”

Goldkuhle, a stained-glass fabricator whose family has restored the cathedral’s windows for decades, had been working with Marshall to turn his vision into reality. Their process began in 2021, when Marshall visited the church to learn about the other windows. The displays intertwine the biblical story and pieces of the American story that cathedral leaders say align with their faith.

After Marshall used coloured pencils to sketch an initial design for the new windows, Goldkuhle travelled to Marshall’s Chicago studio so they could select glass colours to match. Back at home, Goldkuhle then made two test panels and sent them to Marshall to solicit tweaks.

“What I’m trying to do,” Goldkuhle said, “is read his mind and say, ‘Hey, what does this mean in terms of glass, versus a painting where he would mix colours?’”

Marshall visited Goldkuhle’s home in Hanover, Vancouver, this summer to paint the finishing touches on the assembled pieces of glass. The windows were installed in the cathedral in late August and concealed with curtains until their public unveiling.

Taken as a whole, Marshall said, the design is meant to emphasise what he sees as the universally agreeable objective of fairness for all. The words, “Not no no no foul play” conjure many voices seeking the same goal and employ double negatives for emphasis. Reds, oranges and yellows dominate the base of the panels, with greens and blues at the top, to symbolise the peacefulness that comes with climbing closer to an ideal state of being.

“The windows have to speak for themselves in some way,” Marshall said. “They have to not require a curatorial explanation in order for people to understand what they seem to be wanting to do.”

Although the windows will adorn a church, Marshall views the image as purely secular. The characters in the painting appear anonymous – with many of their faces covered – and none are portrayed as more important, like a deity would be, Marshall said. The marchers demanding fairness are everyday people, he said, like those who seek justice in real life.

To Hollerith, the panels reflect the church’s Episcopal faith. The imagery, he said, encapsulates humanity pushing to turn God’s desire for freedom for all into reality.

“There doesn’t need to be a cross in there anywhere, as far as I’m concerned,” said Hollerith, who has overseen the window replacement project. “The theme itself is, I think, very religious.”

A new work by poet Elizabeth Alexander, titled “American Song,” will be inscribed on stone tablets under the windows, replacing previous tablets paying tribute to Lee and Jackson. Alexander, a Pulitzer Prize finalist, recited her work “Praise Song for the Day” at Barack Obama’s first presidential inauguration in 2009.

Her poem for the cathedral, she said, is meant to reflect a constant desire to improve society, even when change requires protest and struggle. In the work, which leans on the theme of light revealing truth, Alexander said she sought to tie together the cathedral’s history, the legacy of the old windows and the companionship of the new windows.

“The poem is not illustrative of the windows, and the windows are not illustrative of the poem,” she said. “But they, I think, really, really harmonise.”

The cathedral, where King preached in 1968, has hosted racial justice-themed programming throughout the window replacement project. Church members attended public forums to discuss the issues that the Confederate windows raised, including what stories are and are not being told in the cathedral’s iconography.

No one has expressed resistance to Marshall’s new windows, Hollerith said. Still, he told Goldkuhle that he wants to shore up the windows from the outside in case someone throws a rock or a brick.

The response to the new art from the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which donated the Lee and Jackson windows in 1953, has been muted. The organisation did not respond to an interview request.

On the organisation’s website, however, President General Jinny Widowski expressed sadness that hate groups have weaponised Confederate imagery but said Confederate monuments “are part of our shared American history and should remain in place”.

“To some, these memorial statues and markers are viewed as divisive and thus unworthy of being allowed to remain in public places,” Widowski wrote. “To others, they simply represent a memorial to our forefathers who fought bravely during four years of war.”

Marshall’s visit to the cathedral to learn about the existing windows was the first time he had ever visited the storied building. The existing art left a mark on him, he said, and the idea of helping enhance the space became appealing.

Marshall was used to making all his own work and had never partnered with a stained-glass fabricator before. It was challenging to depend on someone else to execute his vision, he said.

He also had to adjust to the glass itself having an unfamiliar character. He might pick a colour for the image, he said, only to learn it looks very different in fired glass than it would in paint.

But Marshall said he realised that wasn’t necessarily for the worse.

“Sometimes the thing you end up with,” he said, “is better than what you were asking for in the first place.”

Marisa Iati is a reporter on the general assignment desk at The Washington Post. She previously worked at the Star-Ledger and NJ.com in New Jersey, where she covered municipal mayhem, community issues, education and crime.

This article was first published in The Washington Post

Related Topics: