Wages and Equality: a long way apart

Graphic: Timothy Alexander/African News Agency (ANA) – We need the unambiguous leadership and national commitment to disrupt the Apartheid wage structure of South Africa, the writer says.

By Isobel Frye

On global Anti- Poverty Day, October 17, the UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights Olivier De Schutter spoke out about the terrible increase in poverty due to the global increases in food prices and fuel. De Schutter encouraged governments to index increases to wages and social benefits (like social grants) in line with inflation.

But in South Africa, given the deliberate manner in which wage policy was used during Apartheid to divide white and black workers through civilised and uncivilised work and wages, we need to see even greater commitment than that required by other governments to ensure that the most awful design of Verwoerd and his cronies is forever vanquished or we will allow them to have defeated the democratic dream. But for that we need the unambiguous leadership and national commitment to disrupt the Apartheid wage structure of South Africa.

In South Africa to see the full picture of incomes we need to look at the income breakdown, the main sources of incomes, the nature of wages in the labour market and the levels of social grant income as it pertains to race and gender, and then we need to reflect if this is sustainable, and if not, what needs to be done.

Part of understanding South Africa’s perverse inequality is understanding what constitutes lines of sufficiency or dignity. Having these tools enable one to see what falls beneath this and what is extravagantly above this.

The three poverty lines that StatsSA uses to measure poverty are R663 per person per month as the measure of food or extreme poverty, R945 as a Lower Bound Poverty Line, and R1,417 as being the so-called Upper Bound Poverty Line. A measure of a decent standard of living constructed from broad-based focus groups undertaken by research institutes in South Africa had a 2021 value of R7,911 per person per month. According to these measures, less than 3 percent of South Africans have enough income for a decent life. Over 55 percent of people fall below the Upper Bound Poverty Line, and 25 percent of people live in food or extreme poverty.

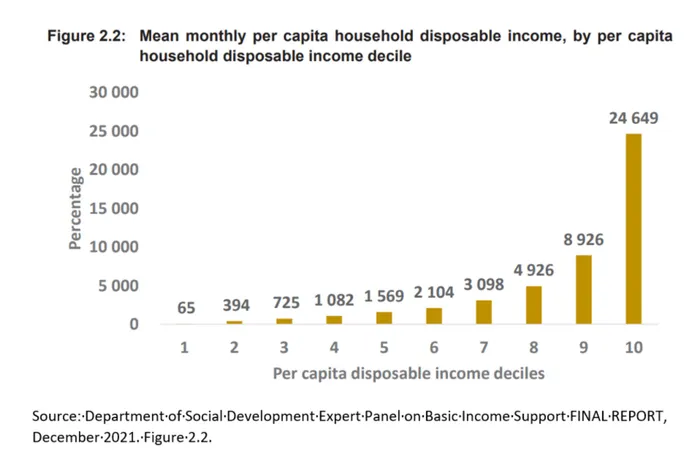

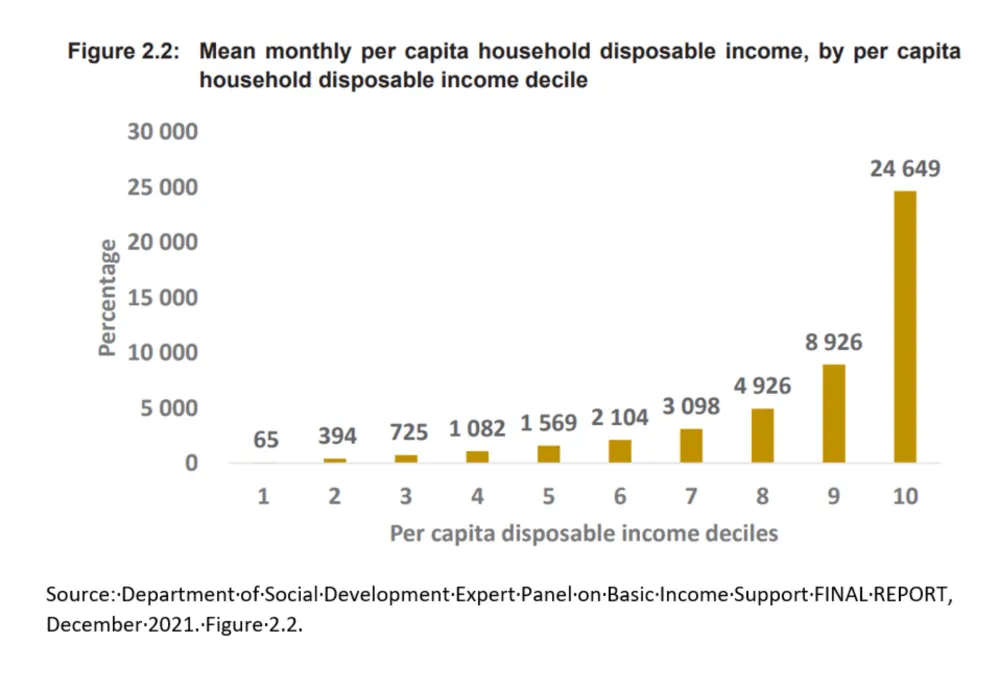

If we bear these measures in mind, we can also see that the richest 10 percent of South Africans have three times the amount of what is needed for a decent life in South Africa, while 80 percent fall far below that level. The figure below shows the massive gap between the incomes of the top income decile and the rest of the country.

What are the main (not sole) sources of income into households in South Africa? Fifty-nine percent of households listed salaries or wages, 51 percent listed social grants and 15 percent listed income from a business.

Wages are still the single most important source of income, although social grants are a close second. Wage inequality is the largest driver of income inequality in South Africa. More than access to land or any other assets like gold or diamonds, it is the underlying unfair distribution of wages that makes South Africa the most unequal country in the world.

Apartheid constructed a contorted labour market reality. Jobs were reserved for whites only and packaged as ‘civilised’ jobs with an equivalency of ‘European’ levels of pay and benefits. Jobs for black people were systematically de-skilled to justify low wages that were deemed sufficient for people with ‘uncivilised’ and reduced needs and desires.

To remember this is extremely painful, the humiliation of being viewed and treated as less, as uncivilised with base, rather than basic needs. What is shocking is that the racialised inequality of wages in the labour market continues today. According to StatsSA, the average monthly wages for employed black Africans between 2011 and 2015 was R6,899, for coloured and Indians/Asians, R9339 and T14235 per month, and for whites, it was R24,646 per month, more than three times as high as for black Africans.

South Africa also has a gender gap index score of 0.78 or between 23 percent to 25 percent.

These levels of incomes determine the lived realities of people living and growing up in these households and the potential and opportunities for the millions of the children growing up in these houses, the future workers and leaders of South Africa.

The income values of social grants are also important if we see their dominant role of providing income to millions of households. In the Eastern Cape, Free State, Mpumalanga and Limpopo, social grants are in fact more significant than salaries or wages.

Because social grants are means tested (poverty targeted) the fact that households are eligible to get grants of itself is a simple, stark proxy indicator of poverty levels in these provinces. But it must also signify to policy makers that these provinces simply don’t have the levels of disposable income needed to support the small businesses that the state is pushing as a critical vehicle to grow the South African economy and jobs.

The maths is simple: almost 19 million people receive grants – excluding the R350 Social Relief of Distress grants. These grant categories are people who are not meant to be working – older people (pensioners), children and people living with disabilities. Almost 5 million people receive the monthly R1990 as pensions and disability grants, while 13 million beneficiaries receive the Child Support Grants of R480 per month.

It is only 6 percent of the Decent Standard of Living referred to above. And this is the worrying fact of the grants – their value. The Child Support Grant is only 72 percent of the poverty line for food poverty or extreme poverty. These are not households that are sustainable, and the lack of income distributed to these households will mire our nation in poverty unless we do something about it. It paints a dismal picture of the extent and depth of the misery of people in a democratic South Africa.

So what is to be done?

Three steps at least signal a way forward to move away from this shameful reality.

Firstly, while the UN Special Rapporteur calls for an indexing of wage and benefit increases to inflation, South Africa needs to first index wages and benefits to a decent standard of living, and intentionally index annual increases above inflation levels to meet income standard.

Secondly, the National Minimum Wage (NMW) that is currently R23,19 per hour or R3,711 per month needs to have a clear pathway to moving towards a living or decent wage, and the Commission needs to annually publish the wage gap between the NMW and top salaries earned in South Africa.

Thirdly, we need to ensure that no person goes without any income. That would first be done through entrenching the Social Relief of Distress grant to all unemployed South Africans and refugees, as the first step in expanding its footprint to provide a decent universal basic income grant.

Globally the pay and conditions of work for vulnerable workers – the precariat – are worsening.

However it is true to say that despite the twin forces of the Constitution and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the sins of the past continue to determine the lives and futures of South Africa, and none more tragically than in the wage structure of the labour market.

Isobel Frye is director of the Social Policy Initiative (SPI).

This article was written exclusively for The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.

Related Topics: