Throwing the Kitchen Sink at Energy Crisis Won’t Stop Load Shedding

Picture: Dumisani Sibeko – An early morning picture taken at Matla Power Station in Mpumalanga Province. President Cyril Ramaphosa’s energy crisis solution is underpinned by privatisation, commercialisation and financialisation, the writer says.

By Trevor Ngwane

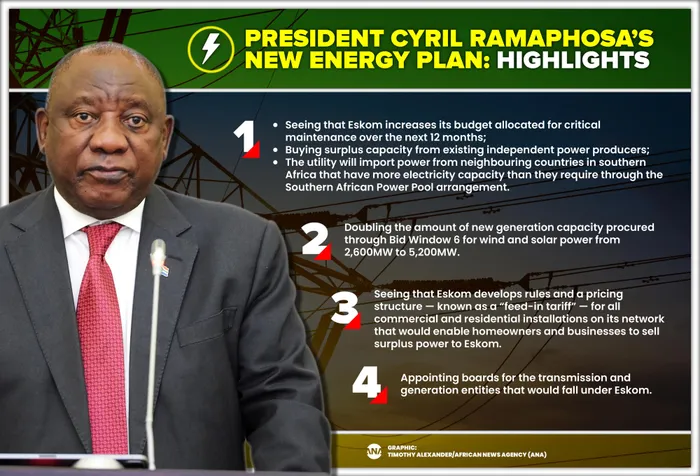

Out of generosity, sycophancy or opportunism, some commentators have called President Cyril Ramaphosa’s hotchpotch plan to address South Africa’s perennial power failures ‘multi-pronged’ or a ‘10-point power crisis plan’.

However, his more than ten proposals to address the energy crisis suggests desperation and seems like throwing the kitchen sink at the problem. The president would do well to take heed of American philosopher and naturalist Henry David Thoreau’s counsel: “It is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things.”

Space does not allow us to list all of Ramaphosa’s motley proposals let alone evaluate each one of them. But, as they say, there is a method behind the madness. The three magic words underpinning the president’s plan are privatisation, commercialisation and financialisation.

These are the building blocks and main features of neoliberalism, that is, capitalist economic policies that make the rich richer and the poorer through the transfer of wealth from the poor to the rich. A major plank of Ramaphosa’s plan is the separation of generation, transmission and distribution in order to attract private capital.

American president Ronald Reagan and British prime minister Margaret ‘The iron lady’ Thatcher are the archetypical champions of neoliberalism. While in office, they led ruthless and relentless attacks on the working class reversing many socioeconomic gains achieved over decades. They waged war on trade unionism, full employment, the welfare state and the regulation of big corporations and financial capital.

They enforced austerity on the majority and empowered the rich ‘one per cent’ of the population. Since then, the masses in the USA, Western Europe, Latin America, Asia and Africa have been struggling to lead secure and comfortable lives.

At the heart of Ramaphosa’s plan is putting all the country’s eggs into one capitalist basket. He imagines that big business is the solution to the energy crisis. The rationale is straight from the Thatcherite neoliberal manual, namely, thou shall as much as possible reduce the role of the state and allow the private sector to take over key social functions, services and industries.

Thus the provision of water, healthcare, education, roads, transport, and so on, must be handed over to the capitalists because they will always do it better than the state. This ‘accumulation by dispossession’ lays the ground for public funds to be channelled into private pockets in the name of efficiency and profit.

About a week before Ramaphosa called the national ‘family meeting’ to announce his proposals, the capitalist lobby group, Business Unity South Africa (BUSA), issued a list of demands telling the president exactly how he should solve the energy crisis. These are uncannily similar to the plan Ramaphosa shared with the family.

A happy Cas Coovadia, the CEO of (BUSA), had his organisation issue a statement the same night the family met, saying how his capitalist constituency is “encouraged” by the president’s comprehensive energy plans and noting that “most proposals from energy experts and the private sector were considered”.

To what extent were the proposals and interests of the working class and the poor considered?

Zwelinzima Vavi, general secretary of the second largest trade union federation, the South African Federation of Trade Unions, complained that his organisation, including the country’s biggest union, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, and the majority union on the platinum belt, the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union, and most of the country’s social movements and community organisations, such as Abahlali baseMjondolo, the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee, the Cry of the Excluded, environmental groups and NGOs were not given a chance to hold audience with the president.

In his enthusiasm to get big business on board, and in the name of solving the energy crisis, Ramaphosa is applying a key policy innovation of neoliberalism: deregulation. All sorts of regulations are going to be removed to facilitate investment and participation of the private sector in the South African energy sector.

This includes relaxing environmental protections and, frighteningly in a country beset by corruption, procurement procedures. It is an open secret that Eskom became the main trough in which the black aspirant bourgeoisie and white monopoly capital filled their insatiable hunger for profits through legal and illegal means. Self-enrichment and greed drove Eskom to the ground.

The solution to the energy crisis in South Africa does not lie in the neoliberal path. What many of those excluded in the president’s consultation process would put forward is the need to put people before profit. To desist from the commodification of electricity and other basic services. To stop the continued burning of fossil fuels which damages the earth.

There must be transition to the use of clean sources of energy. The transition to renewables should be just, it should not penalise employed workers nor rob communities of their livelihoods. No one should be left behind.

Unfortunately, the path chosen by Ramaphosa will not achieve this.

Ngwane is a member of the Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee and the director of the Centre for Sociological Research and Practice at the University of Johannesburg

This article is original to the The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.