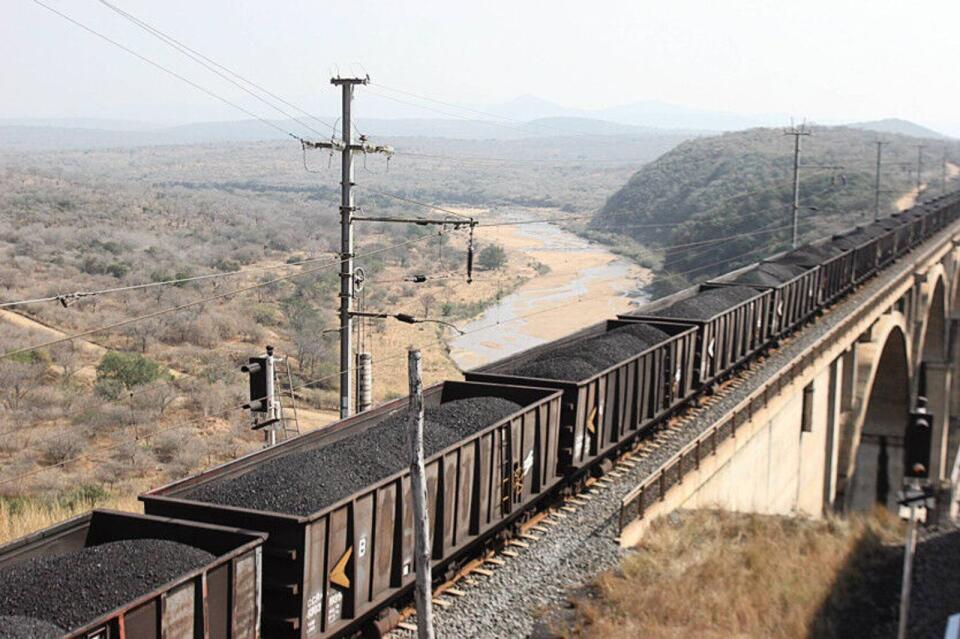

A coal train on Transnet’s dedicated coal line to Richards Bay, KwaZulu-Natal. Picture: African News Agency (ANA)

By Isobel Frye

Quite unexpectedly, coal is currently king as the war in the Ukraine leaves Europe scrambling to meet its energy needs after aggressor Russia threatened to disrupt its historic gas supply. With winter looming, the same northern global leaders who presided over the fossil fuel free commitments of just nine months ago are having to juggle a renegotiation of their exit from coal while remaining committed, at this stage, to the 2030 and 2060 targets. This leaves coal producers in quite the pound seat. But what options does this give South Africa, a country committed to a just transition, and can we bank the current windfall to finance the structural economic redistributive reforms needed to guarantee a sustainable future?

The immediate future is fraught. There is the immediate and medium term fall out of our own energy crisis, and the looming December ANC elective conference, and the early run- ups to the 2024 national and provincial conference that we are witnessing in the courts and conference venues.

South Africa must this time to choose wisely how it plays the coal long game, without squandering recent commitments. Not only can we do so ethically, but we must resist the temptation to spend the coal dividend in a apiece meal fashion. We can and we must capture the gains of the unexpected coal price bonanza just months after we made headlines with the signing at Cop 26 of the $8.5 billion support brokered deal for South Africa’s transition to clean energy. But the proceeds should go directly into the much talked of Sovereign Wealth Fund.

South Africa remains the world’s seventh largest producer of coal. Interestingly, South Africa is both an exporter and an importer of coal. One of our international suppliers to date has been Russia.

The crisis in the north has thrown the line of march towards a fossil -fuel free future into disarray.

Globally there is absolutely no denial of the science of the impact of climate change on the planet, and it is also not questioned that harmful levels of carbon emissions are causing catastrophic global weather. However, the subsequent hostaging by Russia of its gas supply ahead of the European winter has caused a number of governments, led by Germany, to revisit their fossil fuel exit plans and time frames, while at eh same time remaining committed to the extraordinarily successful Cop 26 global commitments to change.

So, what should South Africa to do in this geo-political arena?

It is clear that Europe needs transitional energy sources until its renewable capacity comes on stream. Russian gas can no longer be depended on to be that transitional energy source. South Africa, as a coal producing nation, was richly rewarded for its commitments to phase out its coal production just nine months ago.

It would appear that no one is interested in Europe going without energy this winter. It is also certain that coal buyers would be keen to keep supplies open to prevent coal cartels fixing prices. It does appear that now would be the best time to renegotiate the benefits with some slightly longer window for supplying coal. This could be beneficial all round, but South Africa must negotiate wisely.

We cannot waste this windfall, as we have seen happen over the last three years with the commodities gain.

From Angola and Zimbabwe, there are 25 listed Sovereign Wealth Fund profiles listed in Africa. The Royal Bafokeng Holdings Sovereign Wealth Fund is listed in Johannesburg, South Africa, but unbelievably South Africa still has no listed national sovereign wealth fund.

A sovereign wealth fund would have been the obvious vehicle to bank the recent commodities windfall that provided a very definite silver lining during the Covid-19 disaster. This windfall could have provided a good initial endowment or investment to fund a combination of hard and soft infrastructure builds in years to come.

Daily we can feel the rising jobless numbers, with or without the official statistics, as hunger and hopelessness grow. But South Africa’s conservative macroeconomic policy framework continues to target debt and inflation, rather than economic growth and employment. By keeping debt and inflation levels as constant and as low as possible, our framework simply does not allow for economic growth and therefore the scale of employment growth that we need will never be feasible.

Not only is this undesirable, it is also unconstitutional. The Constitution directs the state to use all available resources for it to rebuild society through the socio-economic rights of access to housing, education, health care and income grants for those who need them. It seems the constitution is important when it protects middle class freedoms, but not that important if used to criticise the current state of inequality and poverty.

But three very clear possible reforms lie ahead.

Firstly, we need to change the macro-economic targets from debt and price stability to economic and employment growth. Secondly, we need to use this space to crowd in economic activity through a decent universal basic income grant, enabling everybody simultaneously to be both producers and consumers, stimulating supply and demand. Thirdly we need to jealously grow the production and manufacturing of goods and services and sustainably locally produced food, with an eye on the vast

African market. With the African Continental Free Trade Area there is unlimited market potential if we can begin to produce goods locally rather than just sell imported goods as we have done in recent years. That will galvanise a renewal of production and new jobs.

We can’t afford to take our eyes off the principles of climate mitigation and adaptation. The regular climate shocks that we have seen escalating are evidence of the fact that nature does not obey geo-political games. We can, however, use this space as Europe dithers, to proceed with the necessary structural reform of the unequal distribution of our national wealth and income. We can chart a bold new direction in terms of the macroeconomic framework that will give us greater sovereign space to implement the scale of economic and industrial rescue plan, and will give the population enough faith to believe in the benefit of representative democracy ahead of 2024.

Frye is the Executive Director at the Social Policy Initiative.

This article is original to The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.