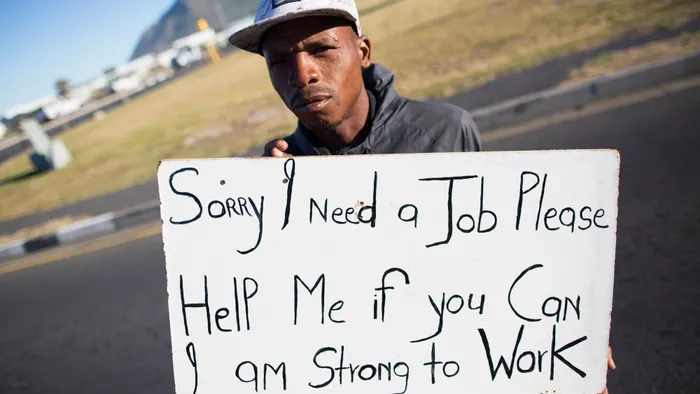

Marginalisation of youth from economy needs urgent action

Picture: Supplied - Young people aged 15-24 and 25-34 are the most vulnerable in South Africa’s labour market today with an unemployment rate of these age groups approaching 61% and 39.9% respectively.

By Sipho Mackenzie

South Africa’s unemployment rate in the first quarter of 2023 was recorded at 32.9%, being the highest in the world. Furthermore, a recently released World Bank report confirmed South Africa to be the most unequal society in the world out of 164 countries explored in the report.

This World Bank report affirmed race to be an important determinant in wealth and education attainment in South Africa. While the guns of our South African freedom fighters were aimed at freedom for the majority population, the bullets clearly missed. Racial inequality and inequity, unemployment and graduate unemployment are sky-rocketing.

As shown in various research, the racial inequities resulting from an oppressive system of apartheid greatly disadvantaged the black majority in South Africa and created a lasting and ongoing social and economic legacy. As a result of this legacy. Black professionals often carry an additional load and a predetermined responsibility to patch the holes created by an unjust past through “black tax”.

Drew Holman’s research report understands black tax as extending to the responsibility one has to financially provide for their family because of them coming from a family whose generations were affected by structural and generational inequalities inside the black communities.

Andile Msibi’s contribution defines it as a financial and social support black employed people in South Africa have to provide to both their families and extended families. One would question why it is called black tax as if the phenomenon only affects black people, but although disparities exist around the world, disparity has colour in South Africa.

Statistically black .families have more members in them (47. 4 million) compared with white (47 million) and Indian (1.5 million) families and are also the most affected by poverty and unemployment. This means that there is often greater financial responsibility for most black professionals.

Furthermore, black tax does not come by virtue of being employed and earning an income because there are child-headed homes, children who take care of their sick grandmothers and unemployed single mothers and fathers who must take care of their families.

This includes labour being done by women to wash clothes, clean houses and other forms of hustling outside of formal employment to contribute to black tax. It is not merely about money, but the act of reciprocity and how one makes up or contributes to the household especially when they are unemployed.

Lehlohonolo shared that despite having a Master’s degree, he was unemployed and mostly got part-time employment. As such, this created a feeling of apathy and helplessness.

Lehlohonolo graduated from the University of Johannesburg and decided to do post-graduate studies to avoid “Kasi Management”.

Kasi Management refers to young people in the townships who are unemployed and thus having to sit at the corner all day, at the Pakistani shops or at home doing nothing productive. It is popularly known as Kasi Management because a lot of youth in townships are subject to it after matric and it has become a norm, a reality.

Poverty and unemployment in correlation still affect most of the population with limited access to opportunities and the economic domain of the country. Young people aged 15-24 and 25-34 are the most vulnerable in South Africa’s labour market today with an unemployment rate of these age groups approaching 61% and 39.9% respectively.

Furthermore, according to Statistics South Africa young people reported to have the highest underemployment rate as compared with older people and are the most vulnerable in the labour market. It is perilous for the country’s social status and sustainable wealth to have such statistics on unemployment, especially on young people. Black Africans are also prone in the South African labour market due to underemployment as they require more working hours.

We must broaden our horizon of black tax for the unemployed and how it affects them.

Professor Anita Cloete shares that “unemployment remains the biggest thief of hope among young people”. Hope in this case is more than the youth seeking employment, but hope for a better life and this is why Lehlohonolo shared that “this is not to say I enjoy black tax, sometimes I wish that I was born into a rich family”. He wished he could get a permanent job and be able to provide for his family to make black tax “easy” but due to that he only gets part-time jobs. That has amplified his anxiety and over-thinking and makes him depressed at times.

Although black tax affects people differently and the severity of it depends on the number of family members and the economic situation they are in, there is a commonality among them.

Whether employed or unemployed, the underlying feeling under black tax in my research was stress, depression and anxiety. With black tax, one cannot satisfy their own personal needs because they either must make up for being unemployed or for being employed.

Many South African black families are still victims to a system of oppression that has prolonged itself in the post-apartheid context, but its effects are experienced through various stressors, that include black tax, whether employed or not. South African youth are suffering a great deal because of not being included in the economic domains of the country and the absence of hope for a positive future.

*Sipho Mackenzie is an MA candidate in the Department of Anthropology and Development Studies at the University of Johannesburg.

Related Topics: