BIG News: Behind the wealth tax idea?

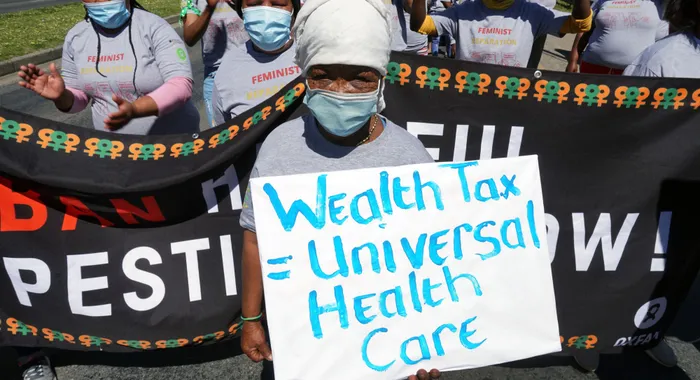

Picture: Ian Landsberg/African News Agency (ANA) - A group of 100 women farm workers and dwellers last year launched the Feminist Reparation Campaign which calls for the introduction of a Wealth Tax for the richest 1% of South Africans to not only finance women farmers’ demands for land, universal quality healthcare, subsidised quality education and a basic income grant but to also address income inequality in the country. Picture:Ian Landsberg.

By Isobel Frye

A BIG (basic income grant) seems to be a pretty mainstream idea in the minds of those who live with poverty daily, if the draft resolutions of the recent 6th ANC National Policy conference is anything to go by.

The active promotion of a wealth tax to fund a BIG was perhaps a little more surprising, but also explains BUSA repeating its fear-mongering on BIG and tax days ahead of the conference.

The idea is attractive: the majority know that inequality must fall, and it is generally agreed that the super-rich can afford it. But before the BIG becomes an anti-rich banner, it is important to understand the societal ailment if the BIG is the correct policy corrective rather than the BIG idea being sacrificed in a battle of class warfare.

Internationally, a Basic Income Grant (BIG) refers to a regular, unconditional, universal, cash transfer (grant) paid to individuals by the state and financed through taxes and other sources, such as revenues from commodities, natural resource royalties and tax windfalls.

A BIG is often viewed as the ultimate social cohesion policy. It creates unity, because everyone gets it. No one goes to bed hungry, so it reduces the impotent rage of starvation. A BIG is the ultimate example of how states can harness the fiscus to stabilise market-driven inequalities. A BIG is a permanent solution. It gets taxed back from people who don’t need it, and there is no sense of ‘graduating ‘or ‘offboarding’ people from the social safety net. The programme exists to provide security and stability. Period.

So why does this the BIG idea appear to strike such fear and loathing in the hearts of leadership?

The existing South African social grants are one of the most successful policies of the government to address people’s basic needs. This does not mean it delivers grants well, just that nothing else comes close to the minimalist relief that grants bring to poor children and pensioners.

It is indeed awful that South Africa has failed to overcome the structural challenges of poverty, unemployment and inequality, but this failure is due to levels of denial and an absolute refusal to undertake the correct policies at scale to end these miserable states of existence. So let us applaud the state for doing fairly well at getting very small amounts of money to the very poor.

But we will always have huge numbers of very poor people precisely because we don’t see poverty as being a problem we can solve, and so we don’t rise to the magnitude of the solution required of giving enough money to the poor to enable poor people to live productive lives that generate virtuous cycles of development and growth. We hand out crumbs, and we punish initiative and innovation by insisting on crippling means tests.

South Africa has just demonstrated that we are able to solve other crises, such as the energy crisis. Deep and shocking though the energy crisis is, we are solving it and we are actually improving on the status quo ante by finally diversifying our energy needs and moving to renewables, hopefully getting a solar panel in every yard.

And Treasury is working out how to absorb Eskom’s R400 billion debt. it can be done.

Let us just focus on inequality.

So why do our leaders reject a solution designed to address over 360 years of inequality, as being too big? Inequality continues to be driven by racial and gendered determinants, as well as historically unredressed thefts of land and livelihoods. Globally it is agreed that inequality reduces human development potential and that it increases violent crime and instability.

This social upheaval makes investment more expensive and so inequality directly drives down growth possibility, fewer jobs are created, and the cycle continues to grow ever deeper. Unless the state intervenes decisively to correct these market and societal imbalances using social and economic policies, South Africa will have either an absolute, violent revolution or will be destroyed by a slow and bitter cancer, eating away from within as we are seeing now. This is not about law enforcement, but about rebuilding a broken nation.

And this brings us to the BIG and the wealth tax idea. South Africa has the highest levels of income inequality in the world. But according to Stats SA’s Inequality Trends report of 2019, wealth inequality is even more outrageous. While the top 10 percent of the population shared about 57 percent of the income between themselves, they have 95 percent of all wealth. In 2014/15 the Gini coefficient measure of wealth inequality was 0.84. 1 is a measure of complete inequality, 0 of complete equality.

And wealth generates more income for the wealthy, over and above their labour. Almost half of total income of the richest 1 percent in South Africa came from their assets. So why should this wealth not be taxed, especially as we see middle class earned incomes are declining. Between 2011 and 2015, earners at the 50th percentile earned 15 percent less in real terms in 2015. Those in the 99th percentile, however, earned 48 percent more in 2015 than they had in 2011.

With food and fuel inflation hitting working and middle class earners, the sense is that they can’t also be taxed more to pay for the BIG, even if they support it. And this inequality fuels a sense of injustice at the fact that the rich are having their cake and eating it.

Mmamaloko Kubayi, chair of the Economic Transformation Committee (ETC) of the ANC, is reported in Sunday Times at the weekend as saying the ANC supports a BIG and a tax on the wealthy to pay for this. She clearly rejected an increase in VAT or income tax citing the levels of financial crisis of the struggling working and middle classes.

Hence the idea of taxing the super wealthy. The acolytes of the wealthy cry that this will make our wealthy move their wealth away. But the super wealthy have already moved most of their assets overseas. They are not using their idle wealth productively to create jobs in the SA economy. Their wealth makes them richer while they sleep, and their conspicuous consumption fuels discontent for the majority.

A universal BIG funded by a tax on the super-wealthy is not a silver bullet. It will not pay the full cost of a decent BIG. And further work needs to be done to link the 12.4 million unemployed people to economic activity. But given the outrageously high levels of wealth inequality in South Africa, a country in which wealth was stolen within so many people’s living memories, a universal BIG paid for by the wealthy ticks enough boxes to be a credible policy to go in with.

Because those who lived surrounded by cake came to sticky ends.

Isobel Frye is executive director of the Social Policy Initiative.

This article is original to the The African. To republish, see terms and conditions.

Related Topics: