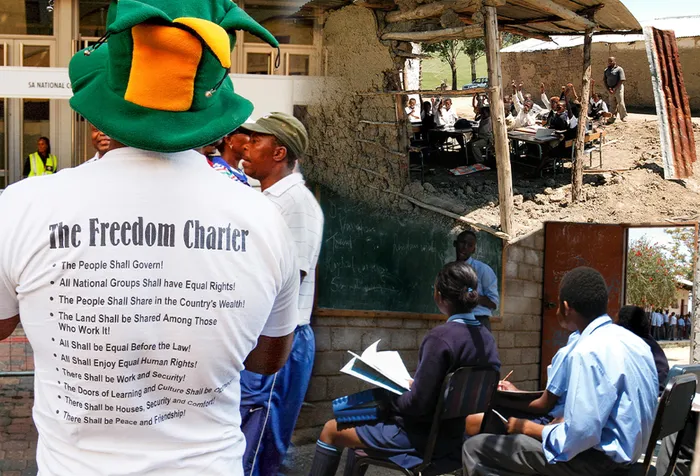

Doors of learning remain shut for rural learners in South Africa

Graphic: Timothy Alexander / African News Agency (ANA)

By Professor Bheki Mngomezulu

On 25 and 26 June 1955, the ANC convened a meeting of the Congress of the People (C.O.P) in Kliptown, Soweto, in Johannesburg. It was at this meeting where the delegates unanimously adopted the Freedom Charter, a document which had been agreed to in principle in 1953 after having been initiated by ZK Mathews.

This document laid a solid foundation for the anticipated democratic South Africa. Among the issues that were covered in the Freedom Charter was human rights. It stated inter alia that “All shall enjoy equal human rights.” Later, it stated that “the doors of learning and of culture shall be opened.”

What was envisaged was that education would be devoid of racial undertones – something that characterised apartheid education. The Charter stated that “Education shall be free, compulsory, universal and equal for all children.” It continued to state that “Higher education and technical training shall be opened to all by means of state allowances and scholarships awarded on the basis of merit.”

Also assumed in this historic document was that education institutions in the form of schools and universities would be well-resourced by the state so that the infrastructure would protect the image and the lives of the learners and the students, enabling them to obtain education in a safe environment.

Given the importance of the Freedom Charter for education, it did not come as a surprise that both the Interim Constitution of 1993 and the subsequent final Constitution of 1996 included the right to education in Chapter 2 of the Bill of Rights. Section 29 of the Constitution, which focuses on education, states that everyone has the right (a) to basic education, including adult basic education, and (b) to further education, which the state, through reasonable measures, must make progressively available and accessible.

The understanding in all these documents was that education was the vehicle that would lead the oppressed masses towards achieving total and real freedom from white oppression. In this regard, education was correctly identified as a human right which needed to be protected by the Constitution.

But accessing quality education is not the only expectation that was envisaged by these documents. Another equally important expectation was that the infrastructure of these schools (and tertiary institutions) was going to be improved. Indeed, this is what the post-apartheid government committed itself to. The fact that previously black schools lagged far behind in terms of infrastructure meant that more resources would be channelled towards bridging this racial gap.

Surely, thinking about something and even articulating the thoughts is one thing. What is particularly important is to translate such thoughts and words into real action so that the intended beneficiaries can witness and enjoy the promises given to them by the documents mentioned above.

With the benefit of hindsight, the following questions arise: to what extent has the school infrastructure in previously disadvantaged schools been improved? In other words, to what extent has the post-apartheid government delivered on its promise contained in the documents mentioned above to address the infrastructure inequalities in schools? If it has fallen short, does this not amount to human rights violation? Two examples below will assist in addressing these questions.

Firstly, starting with the first Minister of Education under the new political dispensation, Professor Sibusiso Bengu, attempts have been made by successive administrative governments to bring back the dignity of previously disadvantaged children in general and black children in particular. This goal has been achieved by renovating some schools that were showing signs of ageing and building new schools where none existed.

But the irrefutable reality is that almost 30 years since the dawn of democracy in 1994, the infrastructure in many schools around the country is an insult to the learners. Some schools have dilapidated infrastructure, while others still yearn for decent classrooms.

This problem is more visible in rural areas and, to some extent, in township schools. The school infrastructure is in a bad state. Some buildings might fall at any time, especially during this time when the weather patterns are unpredictable. This poses a threat to the lives of both the learners and their educators.

While the focus is on the main buildings – the classrooms and the school halls, another important area of concern in terms of the infrastructure is the toilets. Year in and year out, the Department of Basic Education promises to eradicate pit toilets in schools, especially rural schools. Sadly, this promise has not been kept. There are still many schools that use pit toilets.

Already, some learners have lost their lives as a result of this infrastructure challenge. On 20 January 2014, a five-year-old learner Michael Komape of Mahlodumela Primary School in Chebeng Village in the Limpopo province, fell into the pit toilet and lost his life. This was as a result of the Department of Basic Education’s failure to improve the infrastructure in rural and township schools. The incident shook the entire country and attracted condolence messages from all corners.

Believing that the incident could have been avoided had the department delivered on its promise, the family of Komape resolved to sue the Limpopo Department of Education for an amount of R3 million. Although they were fully aware of the fact that no amount of money could bring their child back, the family wanted to achieve two things. Firstly, they wanted to be compensated for the loss of their child. Secondly, they wanted to force the Department of Basic Education to move with speed in addressing this infrastructure backlog.

In a way, something positive came out of this court case. Delivering its judgment, the Limpopo High Court ordered the Limpopo education department to provide a list of all schools still using pit toilets and a plan on how and when the department was going to eradicate pit toilets in all those schools.

On paper, this was a victory for the family. However, the process could not start immediately. There were still other processes to be followed before the court order could be acted upon. One of them was to put the budget in place. Secondly, a service provider (or service providers) had to be appointed. Only then could the process of removing these pit toilets begin.

Secondly, Komape’s school was just one of many across the country with the same challenge. Therefore, while this judgment was specifically focused on the Education Department in Limpopo, the national Department of Basic Education was justifiably implicated since all the schools in the country fall under it. That is why it was cited as one of the respondents in the matter.

Sadly, it looks like the issue of pit toilets is still with us. Just recently, a four-year-old girl at a school in Glen Grey in the Eastern Cape suffered the same fate of losing her life in a pit toilet. The news spread a day later after the child had not returned home from school. This incident did not just reopen the wounds of Komape’s family. It also became an indictment on the Department of Basic Education. Nine years after the 2014 incident, it became clear that pit toilets are still a reality in South African schools.

As the country celebrates Human Rights Month, a few questions arise. Are the rights of children being respected or violated by the government? Do the lives and the rights of rural communities weigh the same as those of urban dwellers? Importantly, is the government serious about implementing the Freedom Charter and the Constitution? If not, what is the recourse?

These questions are important because the people who are currently in government are the ones who fought for freedom and human dignity – both of which were undermined by the Apartheid government. The expectation was that on assuming power, the black political leadership would sympathise and empathise with South Africans in general but rural communities in particular. As things stand, this expectation has not been met.

As reflected in Chapter 2 of the Constitution in the Bill of Rights, the right to life is one of the rights that are enshrined in the Constitution. Therefore, it would not make sense for the country to celebrate Human Rights Month while children who are the future of this country continue to lose their lives in pit toilets.

The two cases cited in this article are just two of many more across the country. However, these cases are enough to emphasise the need for government to address the infrastructure backlog in schools around the country. Failure to do would mean that the government has failed to respect the rights of children and, by extension, the rights of rural and township citizens in the country.

Human Rights Month is an important date in South Africa’s political calendar. It serves as a reminder of the gruesome past that the country has left behind. The onus is on the government to assist the nation to heal by doing the right things – starting with addressing the infrastructure.

*Prof. Bheki Mngomezulu is Director of the Centre for the Advancement of Non-Racialism and Democracy at the Nelson Mandela University.